Chronic pain and health inequalities: what should we do?

by Cass Macgregor and Bronagh Galvin

Chronic pain, also called persistent or long-term pain, usually means pain that has continued for over 3 months, although for some this may be life-long pain.

It is a very broad category, with some chronic pain associated with other health conditions, and is experienced unequally. The severity, occurrence and disabling nature of chronic pain can increase where people experience poverty, and women are more likely than men to have pain. In predominantly white, high-income countries (e.g., UK and US), the occurrence of pain is higher among racially minoritised groups. A recent Public Health England report found that Black people had 10% higher occurrence of pain than any other ethnic group.

Understanding inequalities

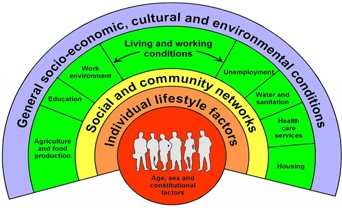

There is no natural law which means that black people living in England or people who grow up in an area of deprivation should have more pain than white people, or those who grow up in more affluent areas. This is why we need to understand more about social, political and economic determinants of health and how they can lead to changes in our experiences of pain. These causes of health inequalities are rooted in unequal distribution of income, power, and wealth, which influence our living and work conditions, our experiences of discrimination (e.g., racism and sexism), and our individual behaviours, lifestyle, and biology. The Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow shown below illustrates these ideas, and how general socio-economic cultural and environmental conditions can have a direct impact on individual people.

Health inequalities are defined as systematic, avoidable and unfair differences in health outcomes between groups of people; they are not naturally occurring differences. Understanding power is vital in understanding how health inequalities materialise. Those who hold more power may have difficulty in recognising and identifying the privilege they hold which can also be an uncomfortable experience. Differences in power may be more obvious to those who are adversely affected, as illustrated by the video below.

Inequalities and lived experience

The experience of poverty and marginalisation may also silence the voices of those affected and lead people to place less value on their own lived knowledge. This is important because at a time where, rightly, there is growing emphasis on ‘lived experience’ we must recognise that not all experiences are the same; access to a ‘voice’ in this way, is not experienced equally. Advocating and planning for inclusion is therefore important.

Health and politics

While daily life can sometimes feel far removed from our politicians, their decisions do affect us. Improvements in health, particularly in our poorest communities, were already slowing prior to the Covid-19 pandemic and cost of living crisis. Public health researchers report growing evidence to show this deterioration in health is linked to austerity policies. Recent news items on the current situation in the UK have included: normalisation of people relying on food banks who are employed full-time; doctors starting to prescribe help with energy bills; recent hospital attendances for hypothermia; GPs reporting the rise of malnutrition cases. Some of our patients tell us they can’t afford to eat nutritious food, pay to take part in exercise such as swimming, or to stay warm, and finances bring extra stress. These examples show the social determinants of health taking effect, and may lead to worsening health inequalities and experiences of pain.

Next steps

Steps can be taken to mitigate for health inequalities. Health care is usually designed by healthy people, with their abilities, literacy and capacity in mind. It doesn’t always meet the needs of patients, particularly those affected by poverty and trauma, the effects of which can be experienced across generations. In Scotland there are ambitious plans for a pain management framework and for public services to be trauma-informed. We should be aware when developing new services if they are only accessible to some, this could widen existing inequalities. In chronic pain physiotherapy in Lanarkshire, we are routinely asking patients who attend about money worries, and signposting to financial inclusion services if indicated.

To adequately address health inequalities, however, we require change to the most powerful determinants of health, which lie outwith the health service and this will require an element of wealth redistribution. We should be concerned over further cuts to local authority and NHS spending in the UK and the impact this is expected to have on health. Yet, hope for change is still possible; other countries have made different choices and continue to do so, in the UK we could do this too. Given this situation, we would like to ask readers, what should we do about health inequalities in chronic pain?

About the authors

Cass Macgregor is a physiotherapist with NHS Lanarkshire and PhD student at Glasgow Caledonian University: Email

Twitter: @MacgCass

Bronagh Galvin is a student on the doctoral physiotherapy programme at Glasgow Caledonian University and is currently conducting an evaluation of asking about money worries in NHSL chronic pain physiotherapy.

Twitter: @bgalvinphysio

We would like to acknowledge the work of others in development of this blog for Pain Concern: David N Blane, Shiv Shanmugam, Kerry Noon, Jackie Walumbe, S. Josephine Pravinkumar, Chris Seenan, Emmanuelle Tulle, Gregory Booth

Pain Concern invited us to develop a blog after engagement with our editorial in the Scandinavian Journal of Pain which covers some of the literature on which this blog is based, and we give the additional relevant literature sources below. Please get in touch with Cass for any particular queries.

Macgregor, C, Blane, D N, Pravinkumar, S J and Booth, G. (2022) Chronic pain and health inequalities: why we need to act. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 2022.

McCartney, G. Popham, F., McMaster, R., Cumbers, A. (2019) Defining health and health inequalities. Public Health. Vol. 172, P 22-30

Marmot, M. (2022) Lower taxes or greater health equity. The Lancet. 400(10349), pp.352-353. Available from Science Direct:

Public Health England (2020) Chronic Pain in Adults 2017. Health Survey for England. Public Health England. Department of Health and Social care.

Scottish Government (2022) Pain Management – service delivery framework and implementation Plan.

The Dahlgren-Whitehead Rainbow – image and explainer

Walsh D, Dundas R, McCartney G, et al. (2022) Bearing the burden of austerity: how do changing mortality rates in the UK compare between men and women? J Epidemiol Community Health. DOI: 10.1136/jech-2022-219645