First Broadcast 30 August 2023

Miriam Brand-Spencer: This is Airing Pain, a programme brought to you by Pain Concern, the UK charity providing information and support for those living with pain, their families and supporters and the health professionals who care for them. I’m Miriam Brand-Spencer. And those of you who listen regularly may have noticed that I am not producer Paul Evans, who is having a well-earned break. I’ve worked behind the scenes on Airing Pain for just over a year now, and hope you enjoy this edition, which explores the complex relationships between dance, self-compassion and pain.

Sarah Hopfinger: Welcome. Take however long you need to settle in to where you are. Throughout this experience feel free to do what is most comfortable for you. You can sit, stand, lie down, stretch, lean, move around. You can snack, drink, make noise, look away, close your eyes. If the content of this performance becomes too much, or for any other reason, you can leave and come back.

You do not need to be a polite audience member. You are invited to do what is most caring for your body and mind. This space shakes its head at pressure and judgement. It wants another way. It’s a space to rest into your body, to acknowledge yourself, however you are, and to settle in to the richness of listening to pain.

Brand-Spencer: Sarah Hopfinger performing in ‘Pain and I’ during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2022.

This edition of Airing Pain explores a complicated relationship between pain, performance and self-compassion. Can the world of dance offer any ideas and techniques for people in pain? And do performers with pain bring something different to an audience? Here’s Paul back in 2022 at the British Pain Society Annual Scientific meeting where he spoke to Victoria Abbott-Fleming, Chair of the Patient Voice Committee at the British Pain Society and the Founder and Chair of the CRPS – that’s Complex Regional Pain Syndrome – charity – Burning Night CRPS Support.

Abbott-Fleming: We support patients and families affected by complex regional pain syndrome. I’ve had it now for 18 years after a fall downstairs.

Paul Evans: Tell me how it affects you.

Abbott-Fleming: I’ve got a lot of severe debilitating pain all the time. I’ve sadly lost both my legs to CRPS because of severe ulceration and skin breakdown. I’ve got a lot of hypersensitivity, so I’ve got to be careful of what clothes I wear and how I, you know, move around and then colour changes, like I get a lot of those and temperature changes. They’re the main things that affect me.

Evans: With all that, obviously, you have management techniques. How do you manage it?

Abbott-Fleming:I use a lot of desensitisation/distraction techniques, so I do a lot of adult colouring and I’ve started to learn to crochet. It’s not very good, but I’m learning [laughs]. It’s just things to keep my mind active and away from thinking about pain all the time. So, I do pacing a lot – well I ‘try’ – I’ll put that in inverted commas. Yeah, we teach it, but it’s actually doing it in person. And sometimes I don’t all the time.

Evans: But I can tell you, as somebody who has a chronic pain condition myself, pacing is such an easy concept and it is so difficult to do.

Abbott-Fleming: It is so true. It really is. You know, the theory behind it is sound, you know what to do and how to do it. But in practice, there are days that I think I really should do a little bit less work – and it is difficult in practice.

Evans: Just explain what pacing is.

Abbott-Fleming: So pacing is trying to do activities and so you don’t do a boom and bust – not all on one day – try to spread them out over several days if necessary. So, if I’m, doing a cooking, I might do a batch of cooking when it’s a good day. So, I know I’ve got something in the freezer for when it’s not so good, but it’s trying to get a steady pace of activity where you’re not doing all at once or nothing at all because it’s just as bad as doing nothing at all.

Evans: The difficult part of pacing is that, for many of us, we have more bad days than we have good days. So, when you have a good day, you think that the sun is on your back. You don’t think I’m better, you think this is good, this is what I want to be.

Abbott-Fleming: Yes. And you also say, I can do it and I’m going to do it. And that’s the problem because you know that you’re going to do it. And most people do whatever their activity is. But thinking strategically a little bit more and maybe setting it out, even if you write it out on a piece of paper, split the activity up, do something, you know, to change it up, and then you may be able to carry on tomorrow.

Evans: We both smiled when the word ‘pacing’ came up because we know how difficult it is. What strategies or techniques do you use to try and do the pacing?

Abbott-Fleming: At first I did use a piece of paper and a grid and I put the activity that I wanted to achieve in that week. I thought at the beginning I could do all of that but then I realised as time went on, that’s too many things all at once. So, then I dropped it down to a lot less but then I added more rest breaks in to try and get through the day and what I did on those good days. I’d know I’d say to myself, ‘Oh, I’ve got to do those three things today’. And then I try and step back and think, ‘No, hang on a minute, I can’t do that because I want to be able to go out tomorrow’. So, I do try to just do that one activity. It is very difficult.

Evans: So, you’re actually planning, you’re looking ahead to what is coming up in the week or the month or whatever – you’re looking ahead and, in order to be able to do those things later in the week, I have to act like this now. Slow down now.

Abbott-Fleming: Yes. And I know sometimes I think, ‘oh, no, I’ll do it now’, because Thursday/Friday might not happen. I might be too tired. But then I think, well, if that’s what my body needs, I need to rest. But it is remembering that you don’t have to get everything done in that one day. There will be other days.

Brand-Spencer: Victoria Abbott Fleming of Burning Night CRPS Support.

Pacing can be tricky for many people living with pain. But what if your job involves physical movement on predetermined days? How does pacing look for people who perform for a living? We spoke to Emma Meehan, a researcher from the Centre of Dance Research at Coventry University. The recording isn’t the clearest. But Emma had some fascinating revelations as to how dancers approach being in pain.

Emma Meehan: It depends on what part of the dance industry you’re in. But often there is this idea that you should be able to push through pain. And so people then mask pain that they have or they don’t treat it seriously – an injury, for example – sometimes it’s good to keep moving, but sometimes, you need to do other things and take care of your body. Probably there’s some learning that the dance science, for example, is looking at – dancers as athletes and doing just the same things as elite athletes would do with pacing their body. The attitudes were more like, the show must go on type of thing [laughs]. The industry should really accommodate all these kinds of artists out there who have developed chronic pain. People I interviewed, their performances are very caring of their bodies. One artist is called Raquel Meseguer, and she creates these horizontal performances – if you need to lie down, you can, and audiences with chronic illness can take part then as well.

But then many of the dance artists I interviewed also felt their performances were about chronic pain and it’s really important for them to have that on stage. But they knew they would still feel pain afterwards, they might have a flare up, for example, but for them it still felt worth it. Something I read from another author as well about this idea that, you know, as long as you’re choosing the pacing, it’s not like you’re a bad person if you don’t pace right. You sometimes say right – for me – it’s worth it to do this and know I’ll have pain afterwards. So, it’s kind of a funny place to be in that sometimes if you’re making the choice of doing something – well you’ll have to spend a week not doing what you could do if you paced yourself.

Brand-Spencer: Emma Meehan, speaking at the British Pain Society Annual Scientific Meeting 2023.

In 2022, we spoke to Tali Foxworthy-Bowers, a choreographer and movement director who took her physical theatre piece Monoslogue to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Monoslogue was about her experience of chronic back pain. So how do performers balance their workload with their health concerns?

Foxworthy-Bowers: Because I grew up in Edinburgh, I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve been able to stay with my grandparents at their house while I’ve been here. So that’s been a real relief because it means that I can go to what feels like quite a safe space every evening and take time out when I need to and kind of decompress. So that’s something that I’m very lucky that I have for the Edinburgh Festival because I think if I was in a share house or it was in a rental, it wouldn’t be the same. I’d really struggle, I think, to kind of feel like I’m able to completely switch off and decompress.

Today was the first show that I did completely by myself, as in setting it up and kind of in charge of everything. And I was quite anxious about it just because everything relies on me and I worry that I can’t give the performance and the piece itself as much attention. But pre-show rituals are quite a big thing for me. I’m definitely not one that can listen to Lady Gaga beforehand and, you know, run and jump around but I’m ….

Brand-Spencer: You’re not really getting psyched up.

Foxworthy-Bowers: …not really getting psyched up at all. I do my physio exercises. One in particular, you know, encompasses the kind of mindful, calming everything down as well and just being, really, on my own and kind of bringing everything back down to earth because it’s so easy to worry about stuff and especially worry that because of the conditions, like you say, of just coming and going so quickly, having such a short get in and get out of the theatre, you know, I can’t cool my body down very well, you know, muscles seizing up afterwards, carrying a heavy bag round with all my equipment in it every day – it’s really easy to worry about things happening to your body like getting another neck spasm and all this kind of stuff. So, I’m quite lucky that my spot is in the morning. Well, lucky in some aspects [laughs] – it’s difficult to get audience members in, but it means that I can have the rest of the day to decompress if I need to. I think if it was an evening slot it would be a different story because I’d be apprehensive about the evening and building up to that and not much time to come back down.

Brand-Spencer: Do you have to consider your body and how you might have to adapt things depending on how you feel?

Foxworthy-Bowers: Yeah, so I talk about getting a neck spasm in the piece and being bedbound for ten days. That actually happened on the first day that I was supposed to create the movement. So, I had, three weeks rehearsal time to create a movement for the piece before my first performance of it. So that obviously took ten days out and the recovery after that added on a few days after that as well. I always have to make considerations and make things slightly smaller in terms of expansiveness and positions and flexibility and things like that. I always have to make them slightly smaller than I would ideally like, but I’m so, so happy with the fact that I can even do this, move with ease and relative pain-free movements. So, I need to keep up the physio body conditioning element of it and, especially, with quick get ins and get outs.

So, I’ve been spending quite a lot of time in the kind of evenings and mornings really just giving my body a bit of extra TLC. I think it’s also knowing that my body is going to take care of itself. I can very easily get into a bit of an anxious spiral about my neck spasming again, especially because when it did so before I was tying my hair up, after I had taught a pilates class so it was completely out of the blue, I had no idea. So, the idea of that maybe happening again does sometimes catch up on me. Also just knowing that this whole piece, that Monoslogue for me, is like a sense of relief and does me a lot of good, as well as pushing my body kind of closer to its limits [laughs]. I think it was my Granny, who I was staying with, also said, you know, if you do need to take a seat it’s quite fitting in the piece so …

Brand-Spencer: You’ve a chair on the stage ..

Foxworthy-Bowers: Yeah, exactly. So don’t worry about it too much sort of thing, which is good, although I’m a bit of a perfectionist when it comes to performing so I don’t think I could have allowed myself do that [laughs] but, you know, I think that if a bit of that was to come out, if I was actually in pain during the performance, then I think it wouldn’t be so much of a worry – like all the audiences that I’ve had have been .. felt really, really nice and supportive. So that makes a big difference I think.

Brand-Evans: Tali was not the only performer in the Edinburgh Fringe in 2022 who had created a show about back pain. We also spoke to Sarah Hopfinger about the creation Pain and I.

Here is Sarah discussing pacing in a slightly noisy part of town in the middle of the world’s largest arts festival.

Hopfinger: I feel like even the idea of pacing has been in my creative process because, well, I guess the intention of going, well, I’m going to work with my body how it is today, and that’s how I’m going to make movement – as well as then actually making the performance, fix things a bit and so I am working with, like, a piece that has a certain choreography and I’m going through that knowing that I can change it if I need to.

As a performer, obviously there can be adrenaline and so it can feel like in my rehearsals I was maybe a little bit more kind to myself – go with my energy. And I think this probably speaks just of part of the issues of the performance world that there’s a bit of me that thinks, ‘I’m just going to go for it today’ [laughs]. A lot of the movement is very gentle and caring for myself but actually there’s some that’s a bit more vigorous and high energy and feels a bit euphoric and like letting go of my body. But I suppose I’m also doing that because I still can move like that, but not all the time – but I can [laughs]. So, it’s like the complexity of it all is kind of there.

Brand-Spencer: And I know you talk a lot in your show about acceptance and a companionship with pain but how do you manage it at the moment on a day-to-day basis? Are there any things you do to try and ease it at all?

Hopfinger: So, I think I’ve spent so much time getting advice about, like, what are the things that are good to do. So, I’ve, like, had physio and I’ve done, like, acupuncture, I’ve done different, like swimming or this or that. But I suppose the things that I do to manage it are the things that I’ve discovered partly myself. So basically, like a walk [laughs]. This is when I don’t have a flare up – it’s like the day-to-day managing.

For me it’s been moving my body in quite a simple way, just walking is key. I do pilates – people told me to do pilates for years and I actually felt really resentful. And then I found a clinical pilates person and yeah, and now I’m quite committed to do my pilates [laughs]. Well, mostly – and I try to do that every day because it’s … even just the movements help, obviously, as well as the, like strengthening of my core, which hopefully means that that’s taking more of the stuff than my back. Yeah, that’s what’s working for me at the moment but I also am aware that it can shift what I need to do.

People mean really well, but I think that can happen so much where it’s like people want to give advice – sometimes it’s really useful, but actually sometimes I think it’s really hard for people that live with chronic pain because we are all different as well. And like, yeah [laughs].

Brand-Spencer: Sarah Hopfinger at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2022.

We’d like to say thanks to everyone who has filled in our short Airing Pain survey so far. Airing Pain is brought to you free of charge, but it’s not free to make. So, it’s important for us to reflect your opinions and receive your guidance to help shape and secure the future editions of Airing Pain. Please take a few minutes to tell us what we’re doing well and not so well by visiting the link in the show description: painconcern.org.uk/airing-pain-survey.

Somatic practices are a mindful style of movement that require the person to focus on the movement and have awareness of their body and the movement within the environment. That might sound a bit confusing, but you’re probably aware of some types of somatic practices, such as Alexander Technique, the Feldenkrais Method and Body Mind centering.

Speaking again to Emma Meehan we heard about her research into somatic practices and what they could offer those living with pain.

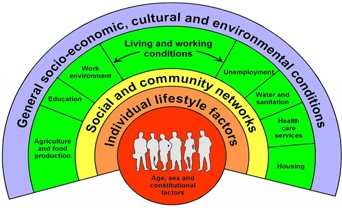

Meehan: The thing about arts-based research – it’s very non-linear. So, I wish I could say my finding is ‘X’ but we kind of like found out a lot of different things so I direct you to an article I co-wrote with a collaborator who’s in nursing, Professor Bernie Carter. We found the various overlaps about the bio-psycho social dimension, this kind of movement is physical, but it also touches on emotion. So, for example, one thing might be about how you inhabit space. Some people might close themselves off when they’re in public space. Some people might take up the middle of the space. So, it’s bound up with how you see yourself. Your identity is linked to how you move. This kind of exploration would open up possibilities for people. The other is social dimension – so moving with other people in practice. So how do I interact with another person? Do I hold myself in a particular way because of my gender, for example.

We recognise there were some things in the somatic practices that would be useful and then other things that might be a problem. So often we work with touch and we recognised from some of the literature that actually, say for example, with fibromyalgia, there might be challenges around touch being painful.

Brand-Spencer: You can find audio, video and text-based somatic practices through the links in the show description and on our site. Do let us and Emma know how you get on.

So, some people find relief by considering how they move. But why do some dancers in chronic pain feel compelled to perform their experiences publicly? The performers that we spoke to emphasised the importance of sharing stories. Can telling and hearing about the lives of others in pain even be a form of self-compassion?

Here’s Paul discussing self-compassion with Jenna Gillettt, a PhD student at the Department of Psychology at the University of Warwick.

Jenna Gillett: Self-compassion is being inwardly kind and understanding towards oneself in the face of pain or failure. Self-compassion, particularly in the context of chronic pain – because what the research is showing is that if you apply a self-compassion intervention, so this would be perhaps a short one-off session where you get an individual who’s living with pain to undergo a procedure such as a self-compassion writing task or something like that, or it could even be 8 or 12 weeks of training in self-compassion. And what we find is that typically people who undergo these self-compassion interventions will have, as you probably imagine, improved self-compassion levels, but also their pain outcomes as well can be improved.

Evans: How would I be taught to have compassion on myself?

Gillett: In short, it’s quite tricky and some people will struggle more than others. Again, is self-compassion a trait or a state? This is another argument in the field. Is it something that you can easily manipulate? Is it something that you can easily induce in people?

One technique – compassion-focused therapy, that is a whole cohort similar to acceptance and commitment therapy – that, again, is sort of really cropping up now and is becoming more readily available. A lot of people just don’t know that these types of therapies exist, let alone being available widespread.

But in terms of the types of tasks that could help with self-compassion, there are tasks such as compassionate writing. So, one that’s frequently used is you would ask an individual if you have pain or if you don’t have pain. You ask an individual to write a letter to their best friend. So, you’re writing this letter and you’re saying all of these great things. You know, ‘you’re kind, you’re amazing, you’re funny’. You know, ‘you’re really doing well with life’, blah, blah, blah. And then you ask the individual to read back that letter and you say, okay, now I want you to write or direct the same letter, the same words to yourself. Think about, as though you’re writing that letter, how all those amazing things you’ve just said about your best friend or your mother, your brother, anybody, all of those things you’ve just said. Now direct that energy back toward yourself. Write the same letter to yourself. Because what we find is, typically as human beings, we are heavily self-critical. We like to criticise ourself and we like to think, ‘I could’ve done better in this’. ‘Oh, that was great. I really smashed that presentation, but I could have done X, Y, Z differently and improved better’. And what you find is that, yeah, typically we need to be kinder to ourselves just across the board more generally, which is why it is such a buzz word at the minute. It’s very much this idea with general mental health, but also specifically with people with pain as well. Being kind to yourself is something that’s definitely important.

Evans: I’m thinking about being in the moment now and what is called ‘catastrophising’.

Gillett: Yes.

Evans: I’m with you now. I’m really enjoying your company and I’m finding it absolutely fascinating. But somewhere in my mind is the nightmare journey I had to get from South Wales to Warwick. And what it’s going to be like when I finish talking to you, having to get back. I need to show some sort of self-compassion to get over that, to enjoy this moment.

Gillett: Yes. Catastrophising is another really interesting part of, particularly for chronic pain, that can shape the experience of someone who lives with pain. Pain catastrophising is a specific type of catastrophising. You know, ‘these thoughts that I had, that that day was really bad’. Or ‘when I went to play with my grandchildren, I really suffered for the next week so I’m going to be a bit more reluctant to do that in the future’. Catastrophising can have a massive effect on peoples’ behaviour, you know, how they feel and what they think about ‘what can I do, what can’t I do’? And that then obviously impacts their lives because, you know, you want to play with your grandchildren on the floor and you want to engage with them, but you’re worried that ‘I’m really going to suffer because of this’. But a lot of the time, you know, we again, human beings, we’re very good at projecting things into the future and looking ahead or looking in the past even. We’re not very good at living right now in this second. So catastrophising is another really important part of what can shape someone’s experiences living with pain.

Evans: So, it’s not the same as somebody saying to you ‘Oh for goodness sake, stop feeling sorry for yourself.’

Gillett: No, not at all. Self-compassion is not just a lack of self-criticism or high self-esteem for example, it’s different. It’s more nuanced than that. One general school of thinking in self-compassion is that it comprises of six different things.

So, you have self-kindness rather than self-criticism. You have mindfulness rather than over-identification. So, this idea that you’re kind of living more in the present – right now what’s happening – rather than going ‘Oh, but I’ve got that big thing next week, and if I’m really rubbish in this thing this week, all that’s going to transpire into next week’. Stop doing that. Be much more present in the moment.

And then the final component to self-compassion is common humanity versus isolation. So common humanity is this idea that everybody at some point experiences pain. Everybody at some point in their life will experience suffering of some description. Isolation is ‘I’m the only person in the world that’s feeling this, I’m the only person in the world that’s feeling really bad and this awful and this intensely’. And, instead, it’s about self-compassion, involves bringing that back to a bit more of a grounded way of thinking in that everybody experiences pain – ‘I’m not alone in this’.

Evans: So, for instance, something I’m criticised for at home is that I can remember every time when I’ve made a mistake in my life from .. from my earliest memories through lying about who dropped the plant pot to my parents to this, that .. I can remember all of those and they all affect me. But many of the good points are fleeting – ‘yes but it only lasted a night’.

Gillett: Yes. Exactly. ‘Oh yes but …’ da da da da da . But it might even be a trait of people who research self-compassion that they are also like that [laughs]. Because I am, too. I can remember all of the bad things very, very vividly. And in general, as human beings, you know, negative experiences do tend to stick with us more because everything is kind of emotionally charged and we have a natural want to do well in things and to be a good person. So that could be one reason why the negative experiences tend to stick more.

But yeah, it’s about also remembering, okay, yeah, that that one thing went wrong. Or I got that one bad review, that one bad comment on this piece of work that I did. But what about all these other things that you’ve done throughout your life that have gone really well? And again, the understanding of unconditional positive regard can come into it as well. You know – you’re worthy of love, acceptance and feeling good regardless of how well you perform or if it’s a bad pain day. If it’s a good pain day, it doesn’t matter. You are still deserving of those good experiences as well.

Brand-Spencer: Jenna Gillett there at the University of Warwick.

Here is Tali again on how writing the show and performing it helped her and her audience.

Foxworthy-Bowers: The process of creating Monoslogue has helped me a lot probably mostly just the writing of it all. So, I wrote the script initially and it started off as a lot of journal entries and so that’s really helped me. But I started writing this piece because I was talking to a friend in college who had chronic hip pain and the amount of genuine pain relief that talking to her about our conditions gave me was unparalleled. So that’s why I started writing it, because I was like, if this … if a one-to-one conversation with someone else can help this much with genuine pain relief, then surely this can help so many other people – and me.

Brand-Spencer: And how have you found that the audience has responded to your piece?

Foxworthy-Bowers: Overall pretty amazingly. The first performance that I did a bit back in March, I was completely overwhelmed afterwards [laughs] and I wasn’t really, you know, surprised – I knew I was going to have a very physical reaction, not only like my reaction, but my reaction to the reactions if that makes sense. Yeah, it’s .. it’s been really amazing and it’s just reinforced my thinking of this is why I’m doing it, because, you know, there’s so many people who have had or have chronic pain or illness or conditions that have come up to me and either explained what they have or just said thank you, or had that same kind of revelation that I had of ‘I’m not going crazy having these thoughts’ because it’s just so funny that no matter what you have, just the similar traits and patterns in your thinking are also similar.

And I think I had one review from the Edinburgh performance where someone said very similarly, you know, that people who haven’t experienced any chronic condition will learn a lot from it and those who have definitely will get relief from it. And that’s just – if you could just tie it up with a ribbon then …then that’s it. Done – you know …

Brand-Spencer: Tali Foxworthy Bowers. I asked Sarah Hopfinger how people close to her could support her.

Hopfinger: I think when I felt, like, really listened to – just somebody knowing that maybe they can’t understand what it is like for me, but being really willing to listen to even like the contradictions of what the experience is even if it is hard for them, they’re not trying to make it better. And that’s felt such a relief. I don’t like to overwhelm someone by saying how difficult it can be. So, I think it’s when I felt like really able just to express the sort of complexities of it or just talk about it. I’ve had so many nice connections with people since I’ve been more open about having chronic pain [laughs] and that’s just been a relief both in my life and my art perspective. It’s like made me feel like the richness of it can come out more often.

Brand-Spencer: You’ve put in a lot of messaging to the audience to be gentle with themselves. How important was it to you to put that message in?

Hopfinger: Like vital really, doing what’s most caring for your body and mind, like people can close their eyes or look away or like change positions or leave and come back. They’re all the things I think that I wish I was always given permission to be able to do, and where it’s really going to be okay if I do it. It’s kind of based on what I would like to feel [laughs]. Yeah. And what does it actually mean to feel welcome.

Brand-Spencer: Sarah Hopfinger in caring for the audience, but what about the performers? How can friends and partners support them? Here’s Tali Foxworthy-Bowers,

Foxworthy-Bowers: My partner Hugo, who helped out with lots of the audio and technical elements of it was here Sunday to Tuesday, and he’s a really strong emotional support for me. So, it was really great to have that at the beginning of my run so that I could get all the tears out while he was here [laughs].

Brand-Spencer: Tali Foxworthy- Bowers. Of course, it’s not only dancers in pain who require support. Here’s Paul again talking to Victoria Abbott-Fleming.

Evans: Do you have a partner? Do you have a husband?

Abbott-Fleming: I do, yes. I have a husband.

Evans: How does he help or hinder pacing?

Abbott-Fleming: Well, that’s a tough one because he sometimes does hinder me. But, generally he … he’s more of a person that will say ‘slow down, you’re doing too much’. Like you said, we both smiled when we heard ‘pacing’ and it’s very easy and I do have a plan. I know there is going to be a day that I miss that. And I know I think now I’m going to do it all. I’m going to have to do it all. And then my husband, he’ll say, ‘No, let’s stick with that plan. You’re going to have a rest this morning and let’s see this afternoon.’ Most of the time, 90% of the time he does help. It’s just that 10%, that he does hinder just a little bit because I think he’s getting in the way.

Evans: This feels so familiar because when I’m trying to pace, when I’m working, actually and not pacing, when I’m blowing myself out, if you like, my wife will say, ‘Stop doing that, stop doing that’. And what I really want to say is ‘I manage myself. You don’t understand’ – which is the wrong thing to say.

Abbott-Fleming: It is. Because they do understand. They feel it just a different way they feel. My husband says exactly the same thing. You know, ‘just slow down. You can do it, but just you can’t do it all at once’. And I do want to turn around sometimes and say, ‘Stop. You don’t know what you’re talking about.’ But actually, he does know what he’s talking about. He probably knows it better than we do, to be honest, because he sees it on the outside. We can only see that one tunnel of what we have to do. We know that we’ve got to pace, but they see how much we actually do. You know, he does say, you know, ‘come on, you’re not going to do that’. And he will stop me. He will.

Brand-Spencer: Victoria Abbott-Fleming. Emma Meehan presented a poster at the British Pain Society Annual Scientific Meeting 2023 on ‘Dancers in Pain: Understanding Agency with Chronic Pain’. Here she discusses the interpersonal aspect of agency with pain, how dancers she spoke to look to each other for support.

Meehan: The poster I’m presenting is about agency with pain and the different dimensions of that. So, they were connecting with peers, but they weren’t doing it necessarily to manage their pain. They were doing it to support each other and have recognition for what they’re going through and to advocate for each other as well. And I think that was part of the problem in front of an audience as well. It’s for audiences with pain and also just the general public to understand a bit more about invisible disabilities that you can’t see and, sometimes audiences would then say, ‘Oh, that’s kind of like something else I experience. It’s not the same thing, but now I’ve a better understanding’. So yeah, at that peer dimension, that’s really important.

Brand-Spencer: Emma Meehan on the interpersonal aspect of managing pain.

I spoke to Sarah about how I resonated with her performance as someone who hasn’t been diagnosed with chronic pain.

Interview with Sarah

I definitely relate to when you were saying about can I be bothered? I was saying to you that with the pilates – that with the stretches – I get shoulder, neck and back pain – on and off – and it’s ‘can I be bothered keeping up’. All of this, all of these stretches doing all these really mundane things – can I be bothered or am I just going to live with this.

Hopfinger: Yeah. yeah. I mean sometimes it can feel quite liberating just being like ‘I can’t be bothered…I can’t be bothered… ‘.

Brand-Spencer: And the bit about not doing enough as well – feeling like you’ve done something with it but there’s more you should be doing.

Hopfinger: Yeah, I know. And that’s an interesting experience of guilt because I think when I do have a flare up, I am trying to find the reason as to why I’m having this flare up. What did I do wrong? What was it that I did that I shouldn’t have done? And such a not very helpful energy in the end [laughs]. But I often go through that process even when I know it’s not helpful. It’s so easy to be like, what could I have done differently? But yeah ..

Brand-Spencer: What kind of reaction have you had from the audiences so far?

Hopfinger: It’s been really nice because lots of people have spoken to me afterwards, but also some people just, like, need their own space. But people have said that it’s been quite moving. I think people who do have chronic pain or something similar have said that they felt quite ‘seen’ by the work, I guess that’s what I felt like I needed. There’s quite a lot of space in the work for people to feel things at different moments or to resonate with different things. And there’s been more crying than I thought but I think it’s been quite good tears because, for some people, I think it’s quite powerful – they haven’t seen that experience of chronic pain, like, represented in art before. Maybe especially with performance and dance it hasn’t been – it has been, but rarely – and people have said that it’s felt quite honest which I hadn’t thought about …but yeah of course it is.

Brand-Spencer: And what are you hoping the audience get out of your performance?

Hopfinger: That’s a really good question. Whatever people do get out of it is what they get out of it. But I want to actually be welcoming and to be caring, kind, because I guess that’s about what feelings or atmospheres do we need in order to be able to acknowledge our pain. For me it’s been a lot about connecting to that kindness or that care, not so that then the pain goes away because I don’t know if it will or won’t. What … what is the feeling that’s needed so that there can be a softer relationship. It’s maybe not always just about acceptance because I also feel like the rejection of it is part of the complexity. So, I suppose I want people to feel like they can breathe with wherever they’re at [laughs]

Brand-Spencer: Sarah Hopfinger. So, if self-compassion, listening and being heard are key, what can charities do to facilitate this form of support?

Victoria Abbott- Fleming again.

Abbott-Fleming: Charities like Pain Concern and Burning Night CRPS – I think we play an integral role in patient support and carers support. Once those patients leave the NHS, yes, they’ve still got chronic pain of whatever condition it is, but once they’ve left that appointment they go home and very often they don’t know where else to turn. So, they do use the internet and finding podcasts like this, or magazines or articles by other people can often make people realise that they’re not alone, that there are others that can help. We do offer support services – helplines, for example, live chat support. We’ve just now started counselling therapy service for patients and families because we understand that mental health is crucial, it does play a big role in pain.

Evans: And for patients with these conditions, all conditions, sometimes they just want to talk to somebody else who’s been through it – and not just the person with the condition – it’s the husbands, it’s the wives, the partners, the parents, the children. It’s so important to have that wealth of experience to talk to.

Abbott-Fleming: It makes a difference. It really does. It’s a big network. It’s a community network effectively.

Pain doesn’t just affect the person with that condition. It will affect the wider group, the families, you know, the home carers, the friends even because they see it all the time and a lot of the time there’s not much they can help them do to help apart from be there, but having organisations like ours, we can support them in that role.

Brand-Spencer: Victoria Abbott-Fleming of Burning Lights CRPF

As in every edition of Airing Pain, I’d like to remind you of the small print – that whilst we in Pain Concern believe the information and opinions on Airing Pain are accurate and sound, based on the best judgments available, you should always consult your health professionals on any matter relating to your health and well-being. They’re the only people who know you and your circumstances and therefore the appropriate action to take on your behalf.

Here’s Emma Meehan on acceptance and the individual aspect of living with pain and how that can be seen in the work of dancers with pain.

Meehan: What inspires the individual aspects, that’s talked a lot more in pain literature anyway, but acceptance of pain – so you’re learning to live with it. That’s actually some way of taking control – dance artists were doing that saying, okay, this is here. How do I dance with it now.

Foxworthy-Bowers: This pain you have, that is your pain. It is part of you now. And it’s true. It becomes part of you, whether you want it or not. But this part is like its own kind of armour, fighting an internal battle that no one else can see while going about your day-to-day life is immensely hard and exhausting.

But of course it is. You are doing two, three times the amount of brain and body work as everyone else. Pain is exhausting. Pain is hard and stubborn. Pain is unpredictable. Pain affects relationships. But we are not our pain.

We own it. OK occasionally it owns us and we have to give up some of our time, energy and tears to its cause. But maybe it means that every other day, every day that is okay and that the pain isn’t too bad, or perhaps, if you’re lucky, the pain isn’t there at all – maybe we see those days as a whole load more beautiful than anyone else. And maybe that’s a gift. Pain is not weakness. Pain is strength. And the way I see it, chronic pain means chronic strength. Or at least that’s what I’m trying to believe.

[APPLAUSE]

Brand-Spencer: The finale there of Tali Foxworthy-Bower’s Monoslogue.

Emma Meehan’s work looked at the impact that various factors can have on the experience of dancers with chronic pain.

The last aspect was agency in the environment. Here she is discussing how the environment can affect how we feel.

Meehan: So, it might be your work environment, your social environment. So, the disability studies – they talk a lot about how environments themselves can be disabling to people. It’s not just that the person has a disability – but the environment is making it impossible for them to live their lives so that a lot of the dance artists were kind of about how do I make an environment that actually works for me? So, I really enjoyed looking at the kind of spaces they were making that made space for people with chronic illness. I kind of liked that it was not hiding pain away but somehow celebrating themselves in public space.

Brand-Spencer: So, the relationship between dance and pain is complicated, and both professional dancers with pain and those from the wider pain community can learn from each other’s experiences, sharing their stories and techniques, and creating wonderful art along the way.

We’d like to thank the British Pain Society for their continuing support and all of the interviewees involved in this edition of Airing Pain. Victoria Abbott-Fleming, Tali Foxworthy-Bowers, Jenna Gillett, Emma Meehan and Sarah Hopfinger. Along with the team here at Pain Concern, producer Paul Evans and broadcast assistant Amy Jupp.

The last word here from Sarah Hopfinger’s Pain and I.

Hopfinger: Dear audience members. Thank you for being who you are. You may need to take your time to move from this experience into the rest of your day. This space doesn’t merely accept you. It needs you to be you for it to be itself. This space shakes its head at pressure and judgement. It wants another way. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

End

Transcribed by Fiona Clunn

Contact us:

General enquiries: info@painconcern.org.uk

Media enquiries: editorial@painconcern.org.uk

Pain Concern Helpline Telephone: 0300 123 0789

Pain Concern Helpline Email: help@painconcern.org.uk

Office Telephone: 0300 102 0162